My parents were married on April Fool’s Day in 1972. In a photo from that day, my mom, freckled and skinny, peers up at the camera through her flower-trimmed veil. Women wearing cotton candy frocks of pastel green or pale peach surround her, organza discs the size of my dad’s record albums pinned to their heads.

“Green and peach”, she sighs. “What was I thinking? Those colors were in style back then.”

In 1985, in our house, those colors are still in style. Our refrigerator is the same minty green: the rotary phone screwed to our kitchen wall, an identical chalky peach. Our living room couch is a mottled pattern of green and orange chenille on a flaxen background. The green refrigerator was there when we moved into the house. But that green and orange couch, the one I think looks like someone spilled pizza on the upholstery, was my mother’s choice. My dad, who selects the dresses his daughters wear to school each day, hates green. He says it remind him of boogers. Unlike my mother’s bridesmaids, my sister and I never wear green.

My dad stares at the picture, a mist of nostalgic tears shrouding his eyes, and he pats the top of my mother’s hand. “My bride wasn’t even old enough to drink at her own reception,” he says.

In each photo from my parent’s wedding, my mother’s expression is the same. Her top lip pursed tightly to conceal her tiny overbite, her head tilted down as she gazes up at the camera lens, eyes wide and eyebrows arched. She never smiles, just holds her mouth slightly agape, showing just the white edges of her top teeth. My father is grinning, goofy. His head protrudes like a balloon from the white bow tied knot at its base and bobs from side to side with merriment. She’s terrified; he’s elated. She’s a 19-year-old Navy brat, and she wants out. Out of a life of arguments and affairs. Out of a life of shielding her younger brother and sister from drunken fury. He’s a 22-year-old Army vet, and he wants in. In to a life of normalcy and calm. In to claim his prize for being lucky enough to live when so many others died.

She’s barely out of high school and he recently left the Army. They didn’t grow up in the same town, or have the same circle of friends. She likes R&B and “shines on the dancefloor”, as her senior high school yearbook describes her. Before going to the Army, he played the drums and was the lead singer in a rock band, spending his weekends and school nights playing in local clubs. They never really explain how they met, least of all how they ended up standing at the altar of his parents’ Lutheran church, surrounded by women in yards of green and peach taffeta, exchanging wedding vows on April Fool’s Day.

They’re two strangers, marrying on a day notorious for personal pranks, who eventually become my parents.

Two summers before my parents’ wedding, the United States and the South Vietnamese governments launched an assault on the Viet Cong organizing in Cambodia’s eastern border with Vietnam. For the months of May and June, the United State military deployed a combination of ground operations and air strikes in an attempt to destroy Viet Cong strongholds hiding out in the neutral country of Cambodia. The South Vietnamese extended their portion of the strike through the month of July.

The Cambodian Incursion, as President Nixon called it, inflamed the anti-war sentiments of students at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio. On May 1st, the day after Nixon announced the beginning of the incursion, students gathered to burn and bury a copy of the Constitution, which, they believed, had been “murdered”. Later that night, a crowd of drunken students roamed the streets of Kent, breaking store windows. The mayor and Governor, nervous over rumors about a radical plot, declared a state of emergency and deployed a riot-gear clad National Guard unit to empty the bars and force hundreds of students back to campus with tear gas. Tensions between college students, the University administration, the local government, and the National Guard tightened as the weekend progressed.

Undeterred, the students scheduled another protest for Monday May 4th. The University administration banned the protest, but despite the ban, two thousand people assembled in the commons by noon to protest the Cambodian Incursion. The crowd of chanting students refused to disburse, throwing rocks as the National Guard, armed with rifles and bayonets, launched tear gas canisters at them. Eventually, as the taunts and rocks continued to fly from the crowd of protesters, the National Guard opened fire on the unarmed crowd of students.1

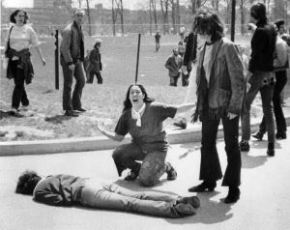

An iconic image from that day shows a teenaged girl, in bell bottoms and sandals, wearing an oversized t-shirt and a white bandana tied around her neck, her long brown hair pushed behind her shoulders, with her arms out, screaming. She kneels at the side of a young man, lying face down on the asphalt. He’s dead; one of the four killed by the National Guard’s attack.

Neil Young sees the photo of the screaming girl, kneeling over the body of a dead college student, and writes the lyrics to the protest song, “Ohio”, released by Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young a month after the Kent State massacre.

Well over a decade after its release, “Ohio” comes on the radio as I ride in the passenger side of my dad’s baby blue Dodge pickup truck. I hear the first note, recognize it right away, and turn up the silver volume knob to sing along. “Tin soldiers and Nixon’s comin / We’re finally on our own / This summer I hear the drummin’ / Four dead in Ohio.” Normally my dad sings along to the radio with me, his rounded baritone harmonizing with my tinny little girl voice. But he is silent, staring out the windshield as I bounce along to the bass line, unseatbelted, in my spot on the blue vinyl bench seat next to him. I hear, and sing, “Ohio” as three separate words, “Oh. Hi. Oh.” and today I finally ask my dad what “Oh. Hi. Oh.” means.

“They’re saying Ohio. It’s a state”, my dad answers.

“What happened there?” I ask

“Some college students got shot. War protesters.” he says.

“Were you there?” I ask. I assumed my dad was present for every major event in rock and roll history. The Beatles concert at Shea Stadium. Woodstock. The Icelandic concert that inspired Led Zepplin’s “The Immigrant Song”.

“No.” he answers. “I was stationed in Virginia at the time.”

Neil Young repeats the line “Four dead in Ohio”, over and over, and my dad continues to look straight ahead, his knobbed knuckles white as he maneuvers the steering wheel. I stop singing along. I have learned two things about my father on this ride: he wasn’t in Oh. Hi. Oh. when the protesters were shot, and he clearly does not like Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young.

My dad seldom talks about his time in the military. I know he was in the Army, that he volunteered because his low draft number guaranteed he would be drafted anyway. And I know that he never went to Vietnam. He was stationed in Virginia for most of his time in the Army. “He was very lucky,” my mother explained when we ask why he didn’t have to go to Vietnam. That was the only explanation ever offered.

Half a century ago, when more than half of adult males smoked regularly, my father had his first cigarette at the age of 13 when he played with his band in clubs on school nights.2 When my sister and I were kids, nobody expected second hand smoke to kill nearly 50,000 people a year in this country, so my dad would smoke in the house.3 Amber glass ashtrays on wooden stands, filled with ash and soot, flanked the orange and green pizza couch. The ashtray in his blue pickup truck was jammed with folded Camel or Benson and Hedges cigarette butts. His acrid cigarette smoke hung in the air of our home, permeating everything – the curtains, the couch cushions, our dog Sherlock’s fur. Each morning my father tied bows that matched the frocks he chose for us to wear to school into our hair and sent my sister and me off to the bus stop with the odor of cigarette smoke trapped in our clothing and hair, the damage to our developing lungs and hearts done. We looked like his little dolls but smelled like his ashtrays.

We moved from Pennsylvania to New Jersey when I was 10, my mom determined to save our new family home from the cigarette smoke that invaded our old home. One ashtray sat in our living room, where my dad sat and smoked his morning cigarette, but all other cigarettes were smoked outside, usually in the garage. This is where I, clad in cut off jeans over flowered tights, find my father one day in May 1992. My green 12-hole Doc Martens boots match my green hair. My dad preferred my pink hair dye, a favorite color to dress my sister and I in when he still had a say over what we wore. He says the green looks like some guy blew his nose in my hair. My lips are painted red; my eyelids lined in a black cat eyed curve . That day, I wear a t-shirt that belonged to my mother when she was a teenager during the Summer of Love. It’s black and reads, “Damn I’m Good” across the front in a sparkly metallic script. I am the same age that my mom was when she wore the t-shirt, 16.

I step out into the garage to find my father smoking by the opened garage door. The metal garage door rail is bent and pinched, so the door can only go half of the way up. A decapitated broom handle is propped underneath the door so it won’t slam shut under its own weight. My dad is crouched down, blowing his cigarette smoke through the open door, the seat of his faded Levi’s resting on the heels of his work boots. Duct tape covers the exposed steel of the wear-worn toe of his boot. I can see the bumps of his spine through his white t-shirt, displaced from the center of his back and curving drastically at the top, his right shoulder blade protruding well above his left. His long blonde hair, the same shade as mine under the fading green dye, covers his crooked shoulders. I always wondered if that twisted spine is what kept him out of Vietnam.

He doesn’t hear me come into the garage, a consequence of inner ear nerve damage brought on by decades of playing and listening to loud rock music. I walk up behind him and place my palm on his hunched back and he doesn’t move or respond to my touch.

“Daddy?” I ask. He exhales another plume of smoke into the late spring sky.

“Yeah?” he replies.

“Are you OK?”

He hunches down lower on his heels. I hear his spine crack under the weight of his drooping head. He says nothing.

“Daddy?” I ask again, the edge of my question spiked with worry.

He lifts his head and sighs.

“I got on a plane in Virginia” he mumbles. “They told me I was going to Germany.”

He clears his throat, stifling the frog sound of a sob. “And I landed in Cambodia.”

**************

1http://speccoll.library.kent.edu/4may70/exhibit/chronology/index.html

2http://www.lung.org/finding-cures/our-research/trend-reports/Tobacco-Trend-Report.pdf.

3http://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/about-smoking/facts-figures/general-smoking-facts.html.